Can the Green New Deal be Truly Equitable?

Ava Cheng | December 16, 2019

Will green jobs really lift people up and out of poverty?

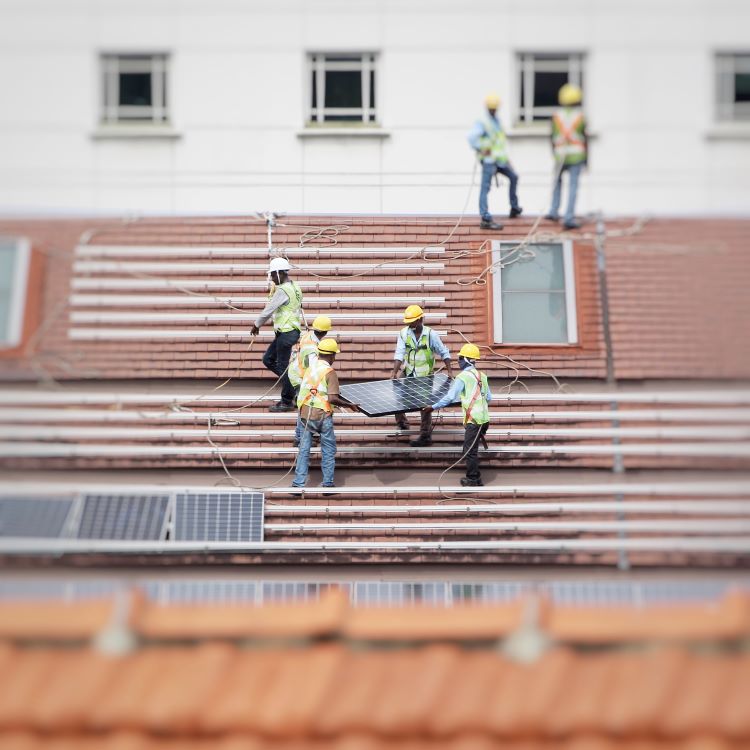

The Green New Deal is a resolution to move towards a future with zero greenhouse gas emissions. It started as a grassroots effort by Sunrise Movement that has garnered huge attention, thanks to vocal leadership from several U.S. Representatives, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others. Within it are two key ideas: 1) that the United States collectively recognizes the immediate need to stop fossil fuel extraction and use because of its impact on the world; 2) to protect citizens from the economic impacts during the abrupt transition away from fossil fuels. The Green New Deal is meant as a comprehensive approach to creating equitable green jobs; that is, jobs that have diverse positions, allow for different levels of education for entry, allow for progression, and have skillsets that transfer across sectors. But are green jobs a strategy to really lift people out of poverty, and are their skill sets transferable and sustainable?

What is a Green Job?

The conversation on green jobs has been an almost two-decade long conversation. Beginnings can be traced to the 2007 United States Green Jobs Act and the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), programs investing in job training, manufacturing upgrades, and technological investments in the clean energy sector.

In the past, green jobs, sometimes referred to as “clean” jobs, were defined by the goods or services produced that either reduced pollution such as greenhouse gases, increased energy efficiency, protected natural resources, or promoted waste reduction and consumption. As they became more common, understanding and measuring green jobs shifted from its focus on counting industrial processes or goods and services.

More recent studies, like that of Barbieri & Consoli, instead measured jobs by occupations being affected by a greening economy. The hope is that this kind of analysis can better capture how a job changes over time as we transition to a more sustainable society, as well as identify new and obsolete jobs. Skill sets in sectors such as transportation, maintenance, and repair for example, would ideally align their knowledge within the growing energy sector.

What do Green Jobs Promise?

Green jobs have been promised to offer fair wages and meaningful work as a response to climate change. They also promise lower educational barriers to entry. More recently, within the context of “The Green New Deal,” these jobs promise disadvantaged communities, particularly those with less formal schooling, the chance to earn not just a fair wage, but a living wage. Professor Ellen Scully-Russ, associate professor at The George Washington University highlighted several barriers to these promises, like preparing the emerging workforce, and shifting existing workforces and their skillsets.

Living wages have been one way of addressing poverty by providing jobs the means to cover expenses and save for the future. The Brookings Institution, a bi-partisan think tank that has been looking at the green economy for the past nine years released a report this year focusing on inclusion and equity within the renewable energy industry. They reference numerous sources that suggest jobs in the energy efficiency and renewable energy sector tend to have lower education requirements. While the literature is not as clear on specific regional wages, the Brookings Institution cited median wages in clean energy between $25-$29, which is $5-10 more an hour than the national average for all hourly wages. This falls within the living wage for some metropolitan areas. For a single parent with a child in California, however, this would not be a living wage in large urban areas like Los Angeles and San Francisco.

A Gap in the Workforce

The Brookings Institution report highlighted the lack of a workforce with medium skill sets such as construction, extraction, and production workers. This implies further efforts are needed to build the pipeline of younger workers. Other challenges related to the workforce gap include modernizing energy science curricula, improving education alignment and training offerings, and expanding training efforts to reach underrepresented workers. So how do we transition these existing green jobs from the medium term to the long term?

The problem is that many green jobs are marketed to be low entry jobs, but really, tend to require greater scientific knowledge and technical skills than the average American job. For green jobs that lean towards environmental management, these jobs require more knowledge in law, government, and clerical tasks; these jobs generally also have less specific and more transferrable skillsets. These jobs require more complex problem-solving skills, and as the green economy continues growing, we run the risk of holding back these industries due to skill shortages. In this transition, Elliot & Lindley highlighted that college graduates, not those with lower levels of formal education, may have the most advantage in the early stages of greening an economy, where new green jobs become available and as existing “regular” jobs become more productive.

Long Term Job Security

Another barrier to growing the pipeline Scully-Russ pointed out is that the United States is not prepared to support jobs going green. These jobs are scattered and dis-organized across the nation and require complex problem-solving that may not have well-defined labor practices and standards to help the industry grow. On-the-job training and close, local coordination from both job and education sectors is highlighted as a very critical part of this transition; otherwise, it may run the risk of preparing students in programs for jobs that do not exist because the industry’s career development path is not clear or consistent.

Specialty by Region: A Solution Forward?

The study by Barbieri & Consoli found that cities with more diverse occupations with skillsets are a strong indicator for green employment growth, both for new jobs and greening of existing ones; regional variety across related occupations is strongly related to employment growth for jobs that are entirely new and greening existing ones. Taking that into consideration, cities and regions that already started focusing on greening are better poised to pivot their younger workforce for this transition. For example, Los Angeles’ sustainability “pLAn” may be one way of addressing the potential disruption as the economy moves away from fossil fuels. Their version explicitly mentioned electric vehicle job training, certificate programs, and private partnerships to increase these jobs and increase green business certifications. It makes a specific note to hire locally and from disadvantaged communities.

With the advent of the “Green New Deal,” there seems to be much hope and promise dependent on the success of green jobs. Introducing new green jobs will most likely not help us equitably transfer to an extraction-free future. It is up to both the public and private sector invest in and support this transition of economies as both new and existing jobs require new skills to adapt. Cities that are primed for this transition generally have a diverse enough job pool and workforce to withstand these changes through cross transfer learning from other jobs. Transitioning to a clean or carbon-free economy will not be a focus on the nation, as it was in the times of The New Deal, but may be at the municipal level, with a focus on regional design and a city’s local economy. Such an approach may allow policy-makers and educators to develop solutions that meet the specific needs of their communities, in the interest of advancing equity.

Ava Cheng is a graduate student in Landscape Architecture at Cal Poly Pomona. Her background in Environmental Studies informs her design approach for a more sustainable future.