Nostalgia Connects Us to Place

The search for identity of Rancho Cucamonga – Can it be found in the past?

Lana Romel Jeries | January 2, 2020

Nostalgia: a sentimental longing or wistful affection for the past, typically for a period or place with happy personal associations.

The role of cultural heritage, and more specifically nostalgia, has been discussed extensively in landscape planning and design. Helen Alumäe, Anu Printsmann and Hannes Palang wrote a chapter in Landscape Interfaces on cultural and historical values in landscape planning, which focused on local peoples’ perception of cultural and historical values in the landscape. Tweed & Sutherland, argued for the role of heritage in fulfilling people’s needs for identity and belonging. While, Evans emphasized the many positive impacts of regeneration of history in designing urban areas, and encouraged culture-led urban strategies. Andrew Jackson Downing also articulated the significant role that history plays in designing the landscape of our cities, when he said:

‘‘To attempt the smallest work in any art, without knowing either the capacities of that art, or the schools, or modes, by which it has previously been characterized, is but to be groping about in a dim twilight, without the power of knowing, even should we be successful in our efforts, the real excellence of our production; or of judging its merit, comparatively, as a work of taste and imagination.’’

DOWNING, A. J. (1921). Landscape gardening. 10th ed., revised by F. A. WAUGH. J. Wiley & Sons: New York.

How do architects, landscape architects, and planners effectively integrate nostalgia without falling into celebration or propaganda? This question was discussed in Raffaella Giannetto’s research on the use of history in landscape architecture nostalgia. She mentions three ways in which history has been used in design. First, it may recall history for the construction of identity, for example when American designers were debating the merits of adopting foreign historical landscape styles. Second, it may manipulate the past and even invent tradition in order to meet certain ideological, or political goals. Third, in which it may be read as memory, whose traces are preserved through design processes and their outcomes. In the third instance, nostalgia can be evaluated through the extent in which it helps transform and improve the present.

Hadiqat As-Samah

One of the best examples Giannetto mentions in her research is Hadiqat As-Samah (Garden of Forgiveness), built in Beirut, Lebanon in 1998. The site had traces of diverse cultures, standing between three Islamic mosques and three Christian churches, it had archaeological excavations from the Greek, Roman, and Ottoman civilizations. The designers utilized that history by highlighting traces of former civilizations that coexisted peacefully, bringing hope for the future of the current war-stricken site. In this case, history was used to prove that living peacefully among multi-ethnic and socially diverse groups is possible.

Showing sensitivity towards a site’s past history and traces of previous use could be critical to design, but it is not necessarily expressed through the literal interpretation of or representation of elements from the past. The strongest takeaway from Hadiqat As-Samah, was not in the design of the garden itself, but in the story that this garden tells and in the statement that it makes.

Rancho Cucamonga’s City Identity

The inland valley city of Rancho Cucamonga, California, experienced a loss of identity as urbanization from Los Angeles encroached on the city from the West in the 1980s. This loss of identity due to urbanization is a story that is all too familiar, in the United States and worldwide.

However, Rancho Cucamonga was faced with the challenge of retaining unique identity since its establishment in 1977. The area was home to three unincorporated communities: Cucamonga, Alta Loma, and Etiwanda. These three villages had an already established history and identity of their own, before they were joined into one city. To this day, these three communities maintain a strong sense of pride in their own histories. Understandably, this can lead to a sense of divide within the city, particularly when other factors such as income and ethnicity contribute to the differences across communities. Cucamonga, Alta Loma, and Etiwanda residents identify with their respective communities perhaps more so than their shared identity as residents of the City of Rancho Cucamonga. What they do have in common, however, is their shared rich agricultural history.

History of Rancho Cucamonga Vineyards

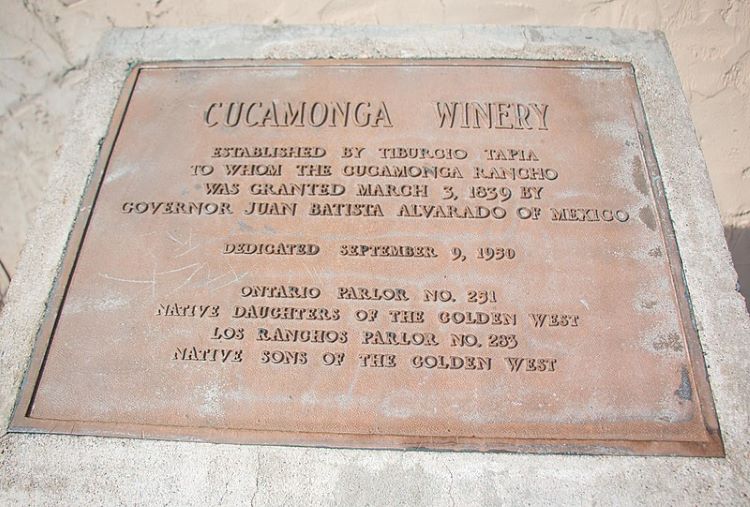

Before the establishment of the City of Rancho Cucamonga vineyards sprawled across the land. Cucamonga valley’s first vineyards were established in 1838 at the Cucamonga Rancho, but most of the Valley’s early prosperity is owed to Secondo Guasti, who founded a Vineyard company in 1883, and grew it to 5,000 thriving vine acres. By the 1940s, Cucamonga valley had more than 40 wineries and between 25,000 and 40,000 acres in vine.

That prosperity was lost when industrial winemaking shifted north, to the San Joaquin Valley and the Cucamonga Valley became part of the expanding metropolitan landscape of Los Angeles. Land prices contributed pressure to convert vines into condominiums and warehouses. By the 1970s, Cucamonga Valley had lost around 30,000 acres of vine. The loss of that vineyard land continues as many of the nation’s oldest vines have disappeared.

Although early settlers planted citrus, olive, peach, and other crops, vineyards and wine making characterized the Cucamonga Valley. The city’s 2010 general plan talks about the importance of maintaining that agricultural heritage and plans to replant grape vines and citrus trees across the city. That interest seems to be shared by the residents of the city as well. A 2015 article by David Allen voiced the pain of watching one of the last citrus groves in the city of Rancho Cucamonga be destroyed and replaced with new development.

Planning for the Future of Rancho Cucamonga

The City of Rancho Cucamonga is now in the process of updating its general plan, which raises the question of how the history of Rancho Cucamonga is relevant to the future plans of the city? Bringing back vineyards is not economically sustainable for Rancho Cucamonga, and may not be the best idea in the face of climate change, where extreme heat and drought are expected to become more frequent in the region. The agricultural history is nonetheless significant to what the city was and has yet to become, and relaying that story to the residents, newcomers and visitors, is of utmost importance.

The way that story is told may be through the preservation of existing vineyards, through wayfinding elements across the city, or through parades and public events done to celebrate that history. A heritage that brings back a cohesive identity to the city grounded in nostalgia; an identity of which all three communities, Alta Loma, Cucamonga, and Etiwanda can be proud.

Lana Romel Jeries is a graduate student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. She has a bachelor’s in Architecture from the German Jordanian University. Her work focuses on designing healthy, well-connected, walkable cities to move towards a future of resiliency.