Dreaming of Los Angeles’ Vacant Lots as Bits of Nature

Macy Dreizler | February 8, 2022

Vacant lots often compel one to imagine, to dream. My dream for the publicly owned vacant lots across Los Angeles, California is to apply urban conservation tactics to transform them into vegetated habitat patches. These patches would provide habitat to enrich urban biodiversity and provide residents with opportunities for recreation and connection with nature. In order to address ecological and environmental justice issues of today, we can invest in green urban infrastructure that benefits all urban residents, human and nonhuman alike.

Vacant Lot Transformations in Los Angeles

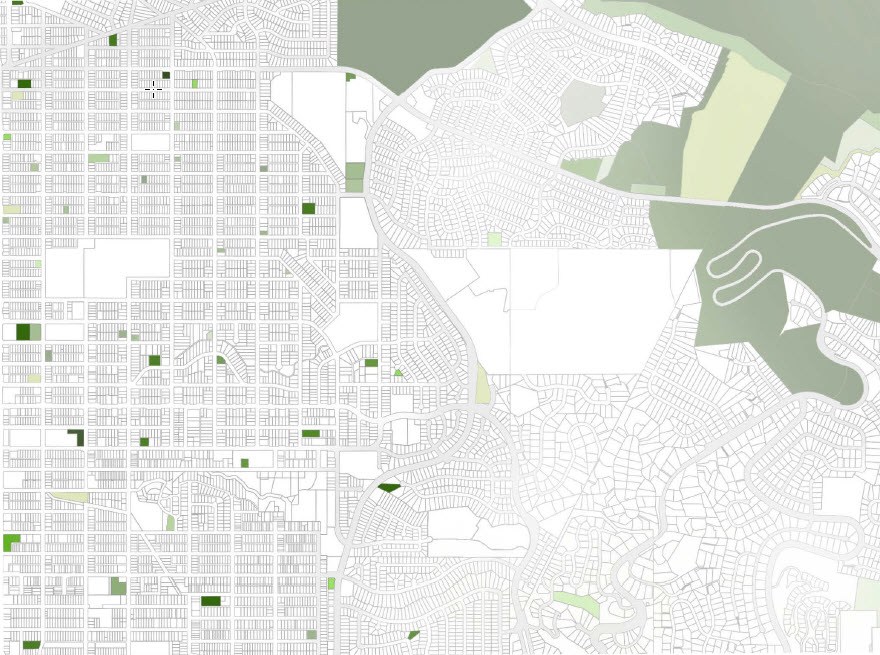

There are approximately 2,000 city-owned vacant lots in Los Angeles with no shortage of government and non-profit groups working to transform them into community assets such as parks or community gardens. In 2012, former mayor Antonio Villaraigosa announced the 50 Parks initiative, a plan to transform small or forgotten parcels into parks in densely populated, park-poor areas. To date, 31 parks have been built with 23 more in the planning and construction phases.

Adopt-a-lot is a collaborative pilot program between the city of Los Angeles, the design non-profit Kounkuey Design Initiative and the Free Lots Angeles Collective. The program transforms vacant lots in neighborhoods with low park acreage or accessibility. This initiative centers community members through participatory design processes and provides usable outdoor space in their community. These programs are important to support the well-documented mental, physical and emotional benefits of parks in urban communities.

These are just a few of the many programs that are working to transform vacant land. Although greatly beneficial, the park redesigns are often characterized by turf, plastic playgrounds and little tree cover— ultimately lacking in ecological value or significant vegetation that could shade the space or provide urban habitat. But publicly-owned vacant land has the capacity to support urban biodiversity in addition to human recreation and connections with nature. Designs that embrace local ecology and increase vegetation and tree cover would benefit all urban residents.

Los Angeles Biodiversity

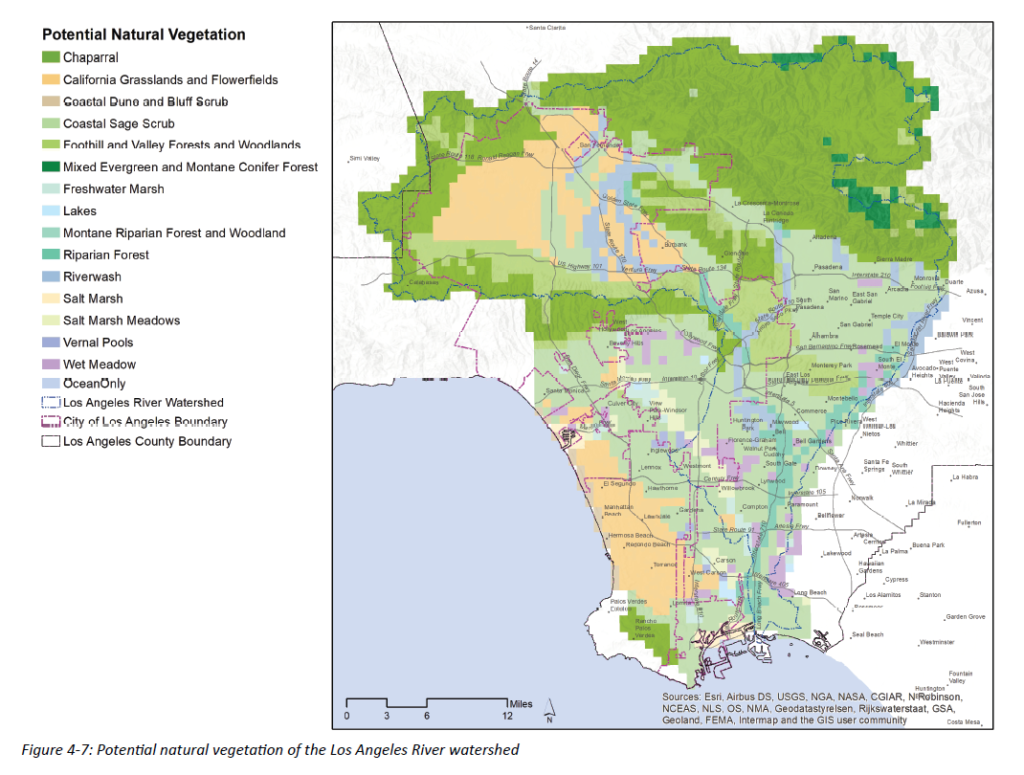

Los Angeles is part of the California Floristic province, one of 36 biodiversity hotspots on Earth. To qualify as a biodiversity hotspot, a region must have a minimum of 1,500 endemic vascular plant species and have lost 70% or more of its original native habitat. Human activities contribute to biodiversity and habitat loss through urban development and expansion, climate change, agriculture, and transportation such as major roads and freeways.

In response to this environmental context, in 2017 the Los Angeles City Council passed Motion CF#15-0499, “Protecting Biodiversity” sponsored by Councilmember Paul Koretz, which called upon various city departments to create a Los Angeles Biodiversity report to better understand the state of biodiversity today. The resulting 2020 Biodiversity report produced by the Los Angeles Sanitation & Environment department demonstrates the city’s commitment to protecting and enhancing urban biodiversity.

Additionally, The Nature Conservancy’s Biodiversity Analysis in Los Angeles published in 2019 aims to both increase the understanding of biodiversity in Los Angeles and also provide a practical tool to improve conservation efforts. A key finding from these reports is that while urban habitat is often fragmented, substantial quantities of native species exist even in the most disturbed, urban study sites.

Despite ongoing research, there is a lack of action when it comes to realizing these findings and applying restoration efforts to the landscape. This inaction could be due to a number of factors including financial constraints, inconsistent municipal priorities or values across city departments, or other important and competing needs for urban land such as affordable housing. Furthermore, maintaining landscapes and meeting bureaucratic regulations and requirements present more challenges for cities.

These dynamics begin to explain why vacant land development has not occurred more frequently across much of the city. The city could benefit from a government agency focused solely on managing vacant land. This entity could unify the disparate approaches that exist in vacant land advocacy and biodiversity research, collaborate with varying departments and social and environmental nonprofits, advocate for solutions and coordinate implementation.

Landscape Mosaics and Conservation Tactics

In his book Land Mosaics, Richard Forman discusses natural processes and urban landscapes, bringing an understanding of urban ecology that we can apply to publicly-owned vacant lots. These lots have the potential to fulfill what he describes as the need for “heterogeneous bits of nature” across the urban matrix. These patches are ideally irregularly-shaped and scattered throughout urban areas to support urban species populations.

Some researchers believe the idea of returning sites to what they might have looked like before urban development is impractical and usually impossible. Instead, Anderson and Minor argue designers and planners can look to the fundamental functions of the ecosystem, as opposed to its assumed pre-development species composition, and design a “hybrid community” based on its current state. It can also be useful to understand how vacant lots already serve as habitat in their current state and what plants already grow there. These place-based tactics could help keep the costs of restoration down through solutions that work with existing conditions while potentially minimizing the need for extensive maintenance and resources. Bioremediation through the use of plants or mushrooms that have the ability to break down environmental pollutants, may be employed on contaminated sites.

Urban Habitat is Not Just for Wildlife

Turo and Gardiner refer to urban conservation as a balancing act because of the social and ecological complexity of urban landscapes. They have found projects are most successful when community partnerships are at the forefront of goal setting and design solutions. The Roots and Routes project, a collaboration between the Field Museum and the Chicago Park District effectively incorporated 20 years of community perspectives into the Burnham Wildlife Corridor plan, which provides social and ecological services including migratory bird habitat, community gathering spaces and youth employment opportunities.

At Esperanza elementary school in Los Angeles, a 2016 collaboration with Los Angeles Audubon Society replaced a vacant asphalt lot with a schoolyard habitat garden. This project joined human and ecological needs through a patch habitat just two miles from downtown Los Angeles and gives students the opportunity to learn from and interact with the garden. Over 60 bird species have been spotted in this small urban green space.

While urban open space can improve the health, environment, climate and economy of an area, anti-displacement strategies may be needed to prevent “environmental gentrification” – a phenomenon where new open space projects increase desirability and thereby displace the very communities the project intended to serve. Tools like the Greening in Place Toolkit advocate for anti-displacement strategies including tenant protections, community ownership and local economic opportunities.

Vacant lots provide an opportunity for emerging urban ecology research to inform a biodiverse and environmentally just Los Angeles. These reimagined bits of nature might serve as case studies to inform experiments with bioremediation and learn from ruderal ecology. A new “Vacant Lot Agency” could amplify the biodiversity research, case studies and work already being done to transform these assets for the benefit of all urban residents – human and non-human alike.

The author would like to acknowledge and thank the peer reviewers and Dr. Kyle Brown and Claire Latane for their help in editing and improving this article.

Macy Dreizler is a graduate student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. She holds a BA in Peace and Conflict studies with a concentration in food justice from UC Berkeley. Her work explores climate resilience, public well-being, ecological restoration and conservation.