Tree Canopy Cover is a Racial Justice Issue

The Case for Equity-Based Tree Planting Guidelines in Communities of Color

Jose G. Gutierrez | February 9, 2021

Urban forests remove air pollutants, lower temperatures, and create wildlife habitat. Planting trees for these purposes is particularly important in communities of color, which often have little tree cover and are frequently adjacent to pollution sources as a result of racist planning practices. These practices make them susceptible to warmer temperatures and worsening air quality resulting from climate change. This is Wilmington’s reality, a Los Angeles community located near the city’s bustling harbor. Wilmington’s population is 89 percent Latino and a quarter of residents live below the Federal Poverty Line, compared to only 17 percent in Los Angeles County as a whole. Serious health disparities also exist in Wilmington. According to the Los Angeles Department of Public Health, obesity rates are more than three times higher than the County’s best performing community. The community is surrounded by freeways clogged with truck traffic from the ports, numerous oil refineries, other industrial uses, and oil-drilling sites scattered throughout its residential neighborhoods.

The benefits of trees are well documented, and touted in many local ordinances and greening plans. Review of existing guidelines in communities neighboring Wilmington reveals promotion of trees for improved air quality, human and ecological health. However planting practice reveals continued preference of trees for their aesthetic qualities and low maintenance costs. To improve human health and ecology through tree planting, agencies need to create equity-based guidelines. An equitable approach recognizes that existing tree guidelines are insufficient in meeting the health and ecological needs of communities of color disproportionately impacted by racist planning practices and the consequences of climate change.

Inequities in Tree Canopy Cover are Rooted in Contrasting Priorities and Historic Practices

Wilmington’s more affluent neighboring communities acknowledge tree planting benefits. The City of Torrance, for example, highlights the ability of trees to absorb carbon dioxide and gases such as sulfur dioxide, while providing oxygen to residents. In the City of Long Beach, tree planting forms part of their sustainability initiative as trees offer “a number of benefits to the surrounding community such as improving air quality, urban cooling, reducing stormwater runoff, [and] increasing property values.”

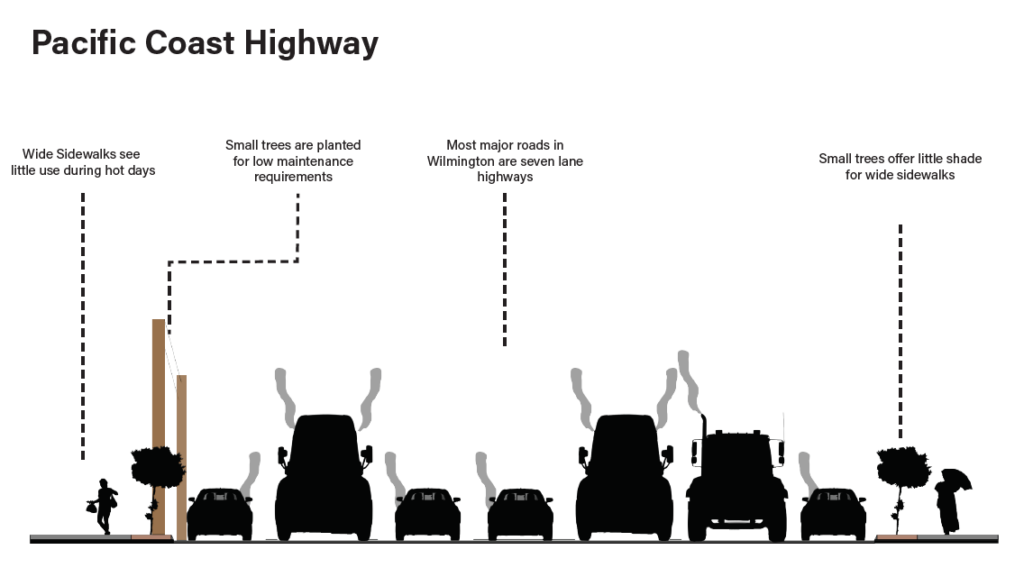

Commonly used street trees found in Wilmington include the Crape Myrtle (Lagerstromia indica), Bronze Loquat (Eriobotria deflexa), and New Zealand Christmas Tree (Metrosideros excelsa). These trees have characteristics desirable to departments concerned with cutting maintenance costs: low water requirements, small spread and height, and a nonaggressive root systems. None are native to Southern California and their comparatively small stature makes significant expansion of tree canopy cover challenging.

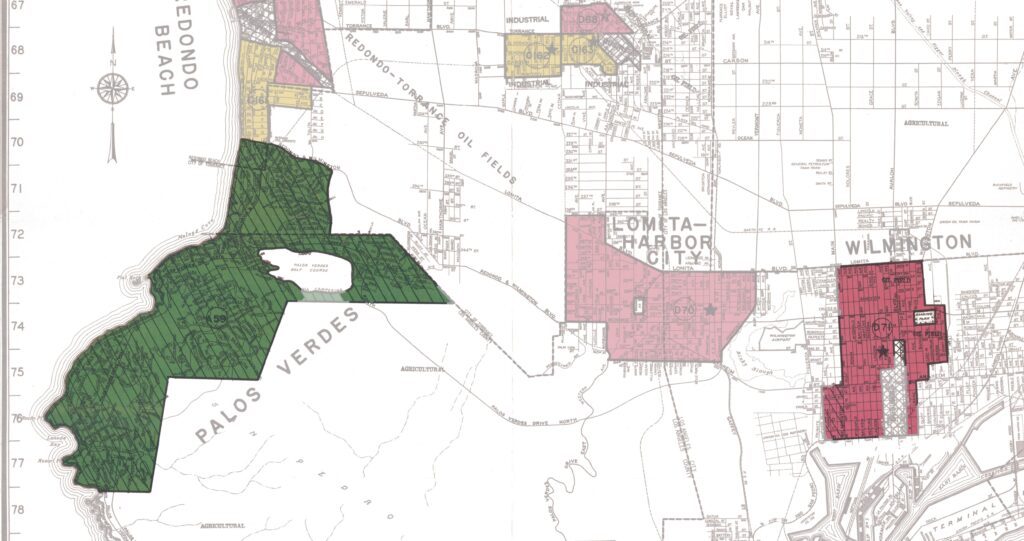

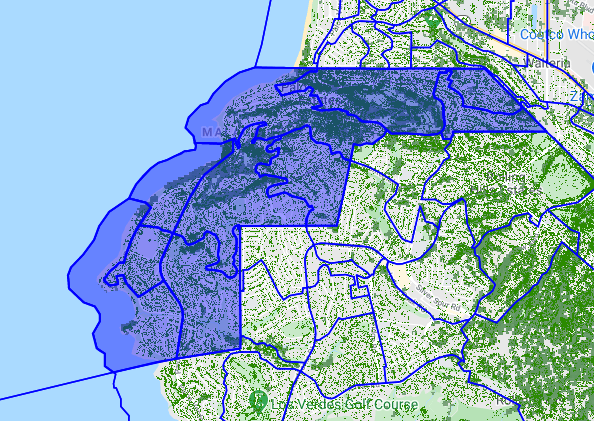

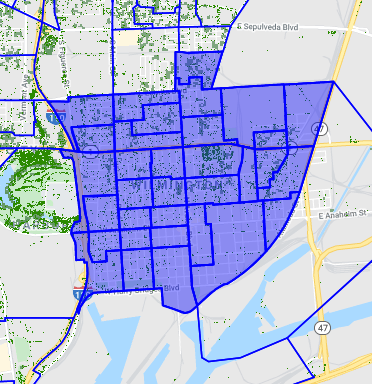

Inequities in tree canopy cover in Southern California are also tied to a racist history. Redlining was the process by which the U.S. government marked working communities of color as “undesirable” for investment in the 1930s. This practice, along with racially restrictive covenants, denied people of color access to Anglo suburbs with better public services, housing stock, and access to greenspaces. Recent studies reveal redlining’s legacy impact on communities of color, which record temperatures up to 5 degrees warmer than Anglo communities with stronger investment ratings. Wilmington, once redlined, has significantly less tree canopy coverage today (4.9%) compared to Palos Verdes Estates, a neighboring, Anglo community, which the government gave an “A” rating (29.5%).

Toward Equity-Based Guidelines

The concentration of air pollutants in Wilmington has made the neighborhood an asthma emergency visit hot spot. As climate change exacerbates the urban heat island effect, tree planting agencies should prioritize trees that provide ample shade and filter air pollutants. Richard Baldauf from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency writes that tree height is important in capturing roadside pollutants along with foliage density and understory shrubs. This combination approach requires a more heterogeneous list of trees and shrubs, a strategy that can also improve wildlife habitat by introducing more native plants.

Equity-based guidelines would also discourage planting trees that emit high levels of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOC). G. Churkina argues that existing urban greening programs do not acknowledge a tree’s potential to worsen air quality through their natural emissions. This point is especially important for guidelines impacting communities like Wilmington, with already impaired air quality. Agencies should move away from planting large quantities of trees known to emit high levels of BVOC, such as New Zealand Christmas Trees, Wheeping Bottlebrush, and Peppermint Tree; All of which are on Tree People’s recommended list of approved street trees for the City of Los Angeles. Tree planting should not contradict the primary goal of cutting unhealthy emissions and dismantling pollution sources.

Significant improvements to public infrastructure need to be made to accommodate trees that meet equity standards. Parkway widths in residential areas should be expanded wherever possible. The parkway is considered the area in front of people’s homes and businesses that is between the sidewalk and the road. Typical parkway widths in Los Angeles are between 4-5’ and this is one reason why small trees are favored in guidelines. Expanding width to 5-8’ allows for trees with larger heights and spread. To further make the planting of larger trees possible, power lines should be placed underground, a solution that has received attention in Los Angeles in recent years in conversations regarding expanding public space access. Road widths should be reduced as well, to expand planter widths and make room for other amenities such as bike lanes. As advocated in the Los Angeles’s Complete Streets Guidelines, center lanes could also turned into wide planted medians, to accommodate large trees.

Existing guidelines are inadequate for resolving tree inequities in working communities of color. Climate change imposes a serious burden on communities like Wilmington—neighborhoods which as a result of historical racist planning policies are unequipped for worsening air quality and hotter temperatures. A comprehensive equity-based expansion of the urban tree canopy in these neighborhoods is a necessary strategy in reversing decades of racist planning practices, tackling climate adversity, improving health and air quality, and restoring ecology.

Jose Guadalupe Gutierrez is a Master of Landscape Architecture Student at Cal Poly Pomona. For the past eight years Jose has worked as a greenspace organizer in Los Angeles, guiding park and community garden projects across the county through the community design process. Jose previously worked with the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust and From Lot to Spot, both LA-based greenspace nonprofits that fight for park equity by building parks, community gardens and planting trees in working communities of color.