Tackling Two Giants with Tiny Alternatives

Patricia Kaihara Arce | January 10, 2020

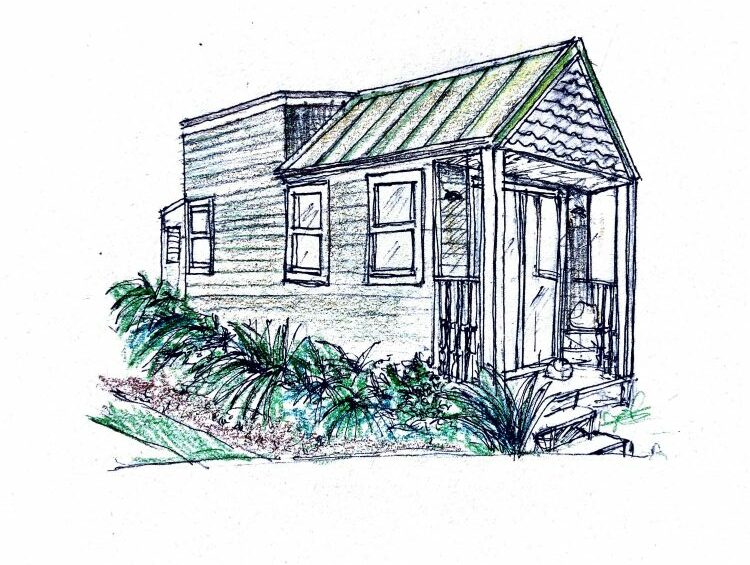

Homelessness and climate change are fundamental challenges facing cities. Can Tiny homes really help?

On any given night in 2018, about 553,000 individuals experienced homelessness in the U.S. A staggering number which is of major concern to our cities, particularly in the face of climate change, another crisis that presents serious challenges to life in our cities. The tiny house movement, which has shown tremendous momentum in the popular media, appears address these two gargantuan issues: homelessness and climate change. But, are these small dwellings truly the panacea to provide new housing with minimal impact to the environment?

According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, homelessness has increased 0.3% from 2017 to 2018 across the country. Skyrocketing prices in real estate in many areas has made housing unattainable by a growing number of individuals and families. Meanwhile, the construction of tiny houses are climbing steadily to help alleviate the burden. The expansion of these dwellings is occurring amid scientific evidence of anthropogenic contributions to climate change, where each built project should be scrutinized to avoid adding unnecessary stress to our warming planet. It is known that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions derived from buildings constitute 40% of the total annual emissions and that household usage of energy is about 21.8% of the US total. Tiny homes as a strategy to house the homeless are often grouped in villages or communities in numbers ranging from 4 to 250. Consequently, any impact of one tiny house is multiplied by many, as these communities are built and replicated.

How Sustainable are Tiny Houses?

Since the turn of the century, communities from coast to coast have been witnessing the reemergence of tiny houses, often as a response to homelessness. These structures of less than 400 square feet have gained vast media coverage with articles, interviews, and compelling stories easily found through a simple internet search. If you follow the advise of Curbed, and browse the web for “tiny house for the homeless”, you will find dozens of related links. Tiny houses are also a trend among individuals seeking to downsize and simplify living arrangements. Tiny house kits can even be purchased online through Amazon. However, despite their popularity and some claims of sustainability, literature is scarce regarding their carbon footprint, including energy efficiency, water conservation, or other green features.

The size of these dwellings are key to energy efficiency. Simple techniques of passive heating and cooling such as orientation, insulation, glazing, use of trees and vegetation, and cross ventilation are easy to implement. For the most part, tiny houses are built as individual and detached units, which favor window placement in every wall to make interior spaces seem larger. This allows increased reception of ambient natural lighting during daylight time, reducing the need of artificial light, and may also support cross ventilation if designed effectively.

Reverend Faith Fowler is the founder of CASS Tiny Homes, a 24-unit community in Detroit, MI. In her book Tiny Homes in a Big City, she tells us that their tiny homes were designed and built with energy efficiency in mind. They might not be “Net Zero,” in their CO2 emissions, but they have included elements to reduce their energy use, focusing mainly in insulating each unit from the Detroit winters by using double-pane windows, and an air tight structure with foam insulation to prevent air filtration. This helps keep ambient temperatures stable in both the summer and winter.

Greenhouse gas emissions are also reduced by implementing solar energy production into the CASS community units. Other programs are also benefiting with this alternative energy source such as Build us Hope in Phoenix, AZ and The Cottages at Hickory Crossing in Austin, TX. Reverend Fowler argues that their 350 square foot units emit 3,502 pounds of CO2 per year, compared to an average American household’s yearly CO2 emissions of 28,636 pounds. This is achieved through a combination of energy efficiency, solar energy production, and a small floor plan.

Other builders report even lower emission numbers. Carlin references the calculations of CO2 emissions done by Jay Shafer, a tiny house builder, who determined his approximately 90 square foot units emit only 900 pounds of CO2 per year.

Research also suggests that living in a tiny house decreases energy consumption because there is no space to accumulate stuff. The other benefit is that tiny houses, because of their small footprint, are usually developed in infill areas, meaning that they can use the infrastructure that is already built, reducing that initial investment, and the resources required to construct supporting infrastructure.

Toward LEED Certification

Beyond energy and water conservation, other features determine the sustainability of a building to then qualify for LEED (Leadership in Energy Efficiency Design) certification. To date, only one tiny home has received LEED certification, and has been named LEEDing Tiny, a great example of how tiny houses can offer sustainable solutions. LEEDing Tiny, is a THOW (Tiny House on Wheels) designed and built through a collaborative effort between Northeast Florida Chapter of USGBC, Eco Relics, and Norsk Tiny Houses, in an effort to provide transitional housing for students and veterans. As described by Patterson in a recent article, the 198 sq. ft. THOW consists of a room, closet, kitchen and bathroom, and includes a small loft; all built with re-purposed materials provided by Eco Relics, a company that recycles construction material from construction sites. Cabinets are made from reclaimed wood. Furthermore, LEED credit was assigned for waste diversion: the construction produced 960 pounds of construction waste and it recycled 557, compared to the average 4,200 produced by construction of an American house. This tiny house also generates its own power through solar panels that are installed combined with a reflective roof to reduce heat trapping. For its LEED qualification LEEDing Tiny was painted with no-VOC paint.

The Need for More Research

These developments are fairly young and their impacts are not clearly documented thus far. However, listening to interviews of beneficiaries, it appears that tiny houses are doing their job in helping population in need, developing a nurturing environment where individuals find a sense of belonging and the support they require to become self-sustaining and leave homelessness behind. Tiny house sizes offer indoor temperature comfort and lighting with less energy, and have the capacity of being sustainable. Nevertheless, the efficiency of these units is yet to be measured and evaluated. It would be meritorious to develop a post occupancy evaluation model to start collecting data at early stages of the projects, and exactly quantify their carbon footprint, and their social impact in a scientific manner.

Patricia Kaihara Arce is a graduate student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at California State Polytechnic University Pomona. With her background in architecture, she wishes to practice in integrating Landscape Architecture into sustainable low income residential buildings.