What Can We Give Back?

Bringing Reciprocity to Newhall’s Public Landscape

Adrian Tenney | January 26, 2021

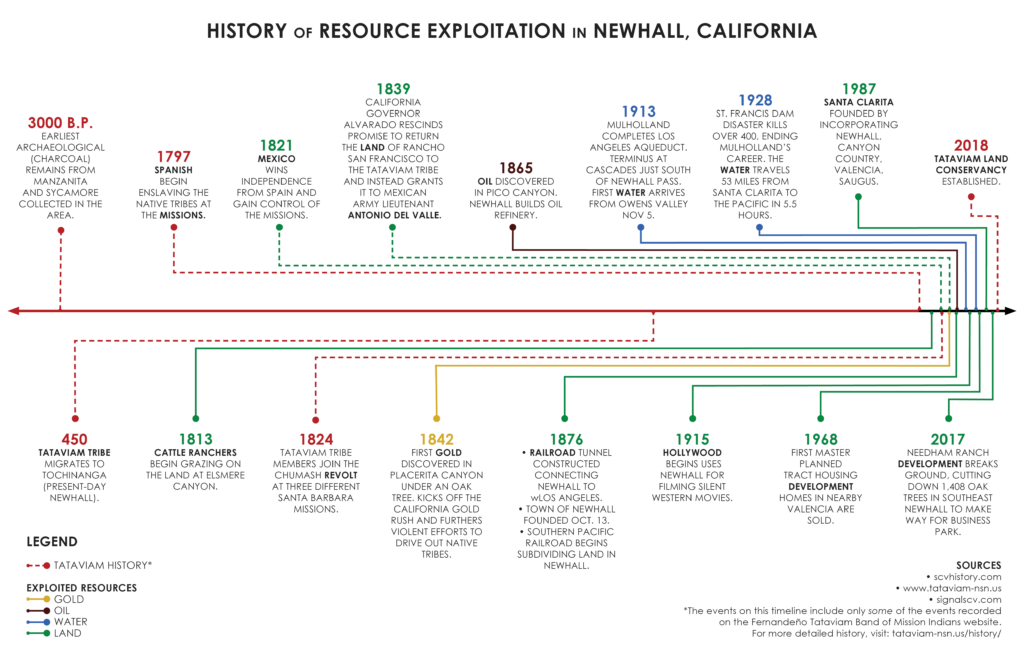

Walking down Main Street in Newhall, a small neighborhood in the City of Santa Clarita, California, is dizzying. The visible and not (yet) visible narratives in the urban form of this neighborhood in one of Los Angeles County’s northernmost cities, reveal a common and unsustainable practice: diminishing the community’s history to reflect a dominant culture based on colonization and exploitation, while erasing Indigenous stories.

This practice has paved an unsustainable path for Newhall, as it has for many U.S. communities. It celebrates exploitation of natural resources for trade, a system known as extraction capitalism, that the nation’s youth are turning against. At the same time, it erases the Indigenous land management practices recognized by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as critical for land regeneration and climate change adaptation and mitigation. Upholding colonial narratives is standard practice across the US, but it is neither socially nor environmentally sustainable. Those who work at the intersections of environmental and social justice must work harder to bring more diverse narratives into the public realm.

Colonial Narratives in Newhall

Subtle, yet destructive colonial narratives are expressed both in terms of what is present in Newhall, as well as what is absent. The region is home to thousands of native Valley Oak (Quercus lobata) and Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) trees. In the 1992 essay Managing Oaks and the Acorn Crop, Helen McCarthy writes that these Oak species produce acorns that were preferred by Southern California tribes. These 400+ year-old Oak trees that provide wildlife habitat, cleaner air, cooler temperatures, and are the symbol on the Santa Clarita city seal, are part of the same Oak groves that the Tataviam people cultivated for over 13 centuries. The tribe used advanced burning, pruning, harvesting, pest control techniques, extensive storage systems and trade networks to manage the acorns. These practices are described in the 1993 book Before the Wilderness: Environmental Management by Native Californians, several other books, and in reports published by the federal government. Yet none of the 16 documents on the Santa Clarita Urban Forestry department website mention Indigenous people or how they shaped the region’s landscape. California Governor Gavin Newsom’s 2019 Executive Order N-15-19 “commends, and honors California Native Americans for … stewarding and protecting this land that we now share.” Acknowledgment is a key first step, and communities such as Santa Clarita should take this step while moving to incorporate Indigenous practices into land management and climate mitigation.

A more obvious manifestation of colonial narratives in Newhall is in the glorification of cowboy culture. This is seen in the Walk of Western Stars, the Cowboy Festival, and the county park named after Hollywood western film star, William S. Hart. The 2005 Old Town Newhall Specific Plan cites “a timeless rustic Western flavor [and] authentic romantic past” capitalizing on Newhall’s history as a Hollywood filming location. But the cowboys memorialized here were not pioneers, but rather actors whose films perpetuate harmful stereotypes and marginalization of Indigenous people. By designing spaces using these fictional western motifs, we misinform the public and omit an important side of history.

In her article Unseen Dimensions of Public Space: Disrupting Colonial Narratives, Indigenous Dakota artist Erin Genia writes that “…monuments, memorials, and public art that people interact with on a regular basis shape perspectives by presenting an erroneous, incomplete, romanticized, tragic, offensive, or entirely missing image of Native Americans to the public. This influences not only how tribal people are seen in society at large, but inevitably, public opinion. Public opinion leads to policy.”

Also preserved in and around Newhall are an old oil refinery, a stagecoach stop, and the Oak of the Golden Dream—all indicators of the city’s role in California’s natural resource extraction. This history is intertwined with the history of violence against Native Americans. By celebrating only the colonists’ side of history, we continue to justify unsustainable land development that continues in the area today.

But there is potential embedded within this landscape. Newhall’s monuments to cowboys and resource exploitation—an erroneous and romanticized image—and failure to acknowledge the Indigenous relationship to the landscape—an entirely missing image—could be transformed into new narratives which do acknowledge and include Indigenous narratives. Including the region’s first people would tell a more balanced, accurate, and compelling history of this vibrant community.

“…monuments, memorials, and public art that people interact with on a regular basis shape perspectives by presenting an erroneous, incomplete, romanticized, tragic, offensive, or entirely missing image of Native Americans to the public. This influences not only how tribal people are seen in society at large, but inevitably, public opinion. Public opinion leads to policy.”

Erin Genia, Unseen Dimensions of Public Space: Disrupting Colonial Narratives, Boston Art Review, 2019.

Decolonizing the Urban Form: Narratives of Reciprocity

According to the United Nations, sustainable development is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” This widely accepted definition is framed by the question: how much can we take from the land? Indigenous Potawatomi scholar Robin Wall Kimmerer proposes reciprocity, not sustainability, as the fundamental law that can guide us through the climate crisis. Kimmerer suggests incorporating reciprocity into our land management practices by asking not what we can take from the land, but rather: what can we give back? In Newhall, there are ample opportunities to incorporate reciprocity. The first and the easiest is to change the narrative around the Oaks to recognize the role of Indigenous people in their cultivation and care. This could include efforts to:

- Educate the public on the history, methods, and significance of Indigenous Oak cultivation

- Update the literature on the city’s website to include texts that reference the role of Indigenous people in oak cultivation and caretaking

- Partner with local environmental organizations such as S.C.O.P.E who recently received a grant to do educational outreach at local schools

- Reach out to the local nature centers to incorporate this information into their programming

Erin Genia suggests another opportunity to decolonize public space is in collaborating with Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) to create public art that amplifies Indigenous voices. She cites the Confluence Project as a successful example, in which Maya Lin collaborated with local tribes and communities. A collaboration like this is conceivable for Newhall. Santa Clarita City Council could start by reaching out to the local Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians which has an active tribal government and provides community services for tribal citizens. They have an educational department; the Yawáyro: Indigenous Awareness and Literacy Program; and recently established a Land Conservancy that is working on preservation, heritage, and education. Board President and Tataviam Tribal Senator, Jesus Alvarez believes “the re-education of the area about the tribe will inspire a richer value to everyone’s experience.”

Finally, there may be opportunity within local events such as the Santa Clarita Cowboy Festival. Drawing thousands of visitors each year, the Cowboy Festival is a lot of barbeque and country music, some flashy lasso tricks, and if kids are lucky they get to drill for oil in sand boxes provided by the primary event sponsor: The California Resources Corporation (yes, an oil and gas production company that has been known to spark wildfires). Although currently paused due to the pandemic, people will eventually flock to the Cowboy Festival as they have for over 25 years. Funding could be set aside to hire Indigenous storytellers and educators, to give the Fernandeño Tataviam Band of Mission Indians a prominent space at the festival, to promote the Tataviam Land Conservancy efforts, and to have a booth dedicated towards understanding the reciprocal effects between Indigenous people and the region’s oak trees.

By reframing these narratives Newhall can honor the knowledge and practices of Native people, increase public understanding, and cultivate a future generation of Oak protectors. This could be a step towards returning the gifts we receive from the Oak trees and help make the City’s Oak preservation efforts better understood and protected by the public. City leaders could promote a culture of reciprocity over extraction and follow through with IPCC recommendations. Then Newhall could begin its long-term path to reciprocity.

The author would like to thank the peer reviewers and acknowledge the editors Claire Latané and Kyle D. Brown for their contributions, which helped improve this article significantly.

Adrian Tenney is a graduate student in the Master of Landscape Architecture program at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.