The Labor behind our landscapes: Communication between Design Professions and Landscape Workers

Eduardo Baca | May 25, 2022

I hear my alarm. It is set for 4 A.M. for the 19th day in a row. I try to open my eyes, but they feel glued shut. I lay still and contemplate calling in sick. Somehow, I find the strength to swing my legs off the side of the bed. Joints crack and pop as I walk towards the coffee pot. My body reminds me why I’ve returned to school.

While studying, I have been a landscape maintenance foreman at a golf club in Orange County, California. Physically drained and physically damaged from tirelessly shoveling through rooted and dense rocky soil. I cannot imagine how some of my coworkers have endured twenty years of this type of labor. Twenty years of highly repetitive motion, high impact activities, high exposure to the sun, wind and rain. Not knowing what each day has in store, yet knowing it will be hard on my body.

As a graduate student in Landscape Architecture, I have experienced a disconnect between two professions: those who design landscapes, and the professionals who install and maintain those landscapes. While the relationship between these sectors has had renewed perspectives from forward thinking firms and landscape architects, hierarchical divisions are persistent and the work and expert knowledge of installers and landscape maintenance workers is often devalued.

Landscape Roles

Hierarchical roles across landscape sectors compartmentalize decision making and exclude those not involved in the process. These roles are structured to impose power, and often result in separation and difference between sectors. At my work, I have firsthand experience being left out of the decision-making process.

In a typical design, the landscape architect selects the location and type of plants installed to meet specific design objectives. The decisions made by a landscape architect are usually made far away from the site, with little to no knowledge about the crew that will install and maintain the project.

Installation crews follow the guidance from construction documents and planting plans. Flags are first placed to indicate planting location. This vital step of the installation process is where design and reality intersect. Often I observe non-verbal dissatisfaction from my co-workers as they resist from commenting about the poor placement of flags. This dissatisfaction, yet reluctance to intervene, illustrates the hierarchical roles that have been internalized among the workers. While adjustments are as easy as moving a flag, installers are not confident with their own expert opinion, knowing it may be contrary to those higher up in the hierarchy. Thus they refrain from offering input out of fear of losing their job.

Fear in Landscape Labor

Throughout my time as a Foreman, I have had the pleasure of working with professional and talented landscape workers. Two such workers I know have a combined 30 years of landscape installation and landscape maintenance experience. I will call them Pedro and Cornelio for the purposes of this article. Walking the grounds of the clubhouse, Pedro and Cornelio’s landscape installation and maintenance leave me in awe. The landscape looks controlled yet natural and untouched. Pedro and Cornelio’s hard work achieves an illusion of a built landscape appearing natural and self-sustaining. They achieve this illusion by cultivating an intimate knowledge of each planting areas soil type, irrigation issues and needs, sun and shade observation, and pruning schedule. Despite this talent and dedication, they spend their days fearful of being seen taking a break between raking or shoveling, making a wrong cut during pruning, or moving flags before an installation project.

One day, standing next to Cornelio during an installation project, I mentioned that each flag represented a certain plant, and the flags were placed by the guidance of the planting plan given to us by the landscape architect. I asked him, “What would you change about the placement of these flags?”

He was reluctant to answer. “I don’t know, however they want,” Cornelio deferred, I did not push for an answer. Cornelio shared, “Employees have been fired for voicing their opinion, and whatever the superintendent says goes.”

High turnover in landscape labor professions is bad for business, as it leads to inconsistencies of landscape outcomes. Employees who are fearful are less likely to stay in a position for the long term, and the fear of losing a job for speaking up highlights how the experience and knowledge of landscape workers is devalued.

Maintenance-Minded Design

Recently, I was asked to finish a clubhouse planting project at the country club. Throughout the project, I was determined to pick Cornelio and Pedro’s brain to make the project as successful as possible. They had been subjected to top-down coercive management methods, which I had also experienced, even in my position as Foreman. The experience leaves you feeling like a mere tool, dehumanized, and excluded from decision-making.

I stood in front of the project area with them, staring at the flags which marked the plant locations per the planting plan and stated, “I want you to feel free to make changes. If the superintendent does not like it, I’m the one to blame. Please tell me what you would do differently.” I handed the flags over with complete trust in their abilities. Pedro was the first to move flags around, and Cornelio joined shortly after.

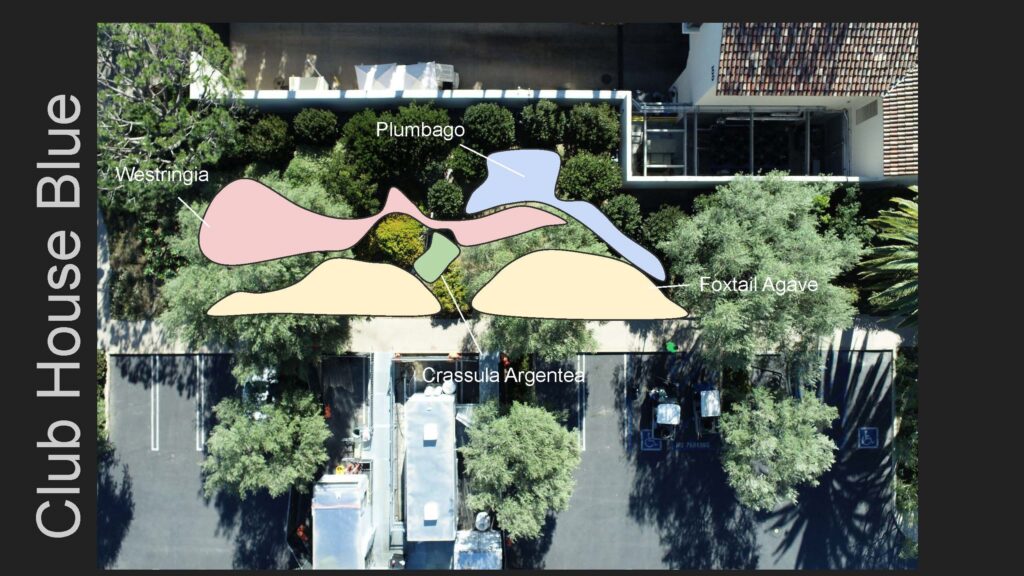

When they had completed transforming the planting design, we stepped back to discuss the changes they made. The spatial arrangement of the planting area came from Pedro walking and imagining various height levels of plants and sight lines from a walkway between the clubhouse and fitness center. Cornelio assisted by standing in the middle of the planting area to signify the height of a mature ‘Plumbago’ (Plumbago auriculata). The same was done with the ‘Westringia’ (Westringia fruticosa). ‘Foxtail Agave’ (Agave attenuata) were added to bring another spatial element to the planting area. The ‘Foxtail Agave’ allowed for greater connection with adjacent planting areas, attempting to seamlessly match existing sight lines to create a continuous walking experience. Plant spacing allowed room to grow into maturity while realizing some instant gratification of the finished project would impress the ultimate customers, both members and the superintendent. Pedro and Cornelio planned to adjust the planter to allow for plant maturity within the next couple of years.

Maintenance was a major concern for Pedro and Cornelio. All the hard work of removing leaf litter from planting areas, dead heading plants, pruning, and watering, all came from their dedication to produce a high-quality landscape. Their selection and quantity of each plant rested on reducing maintenance requirements while maintaining design cohesiveness. Cornelio explained, “With the ‘Plumbago’, ‘Westringia’, and ‘Foxtail Agave’, we will have more time to spend on other areas.”

Once we began installing the plants, I noticed a difference in this installation. Cornelio and Pedro were smiling, and I instantly knew how they felt.

Project success matters as much on the last day of installation, as it does 10 to 15 years from project completion. To ensure the quality of a design is preserved throughout the life of a project, early and consistent communication with maintenance workers at all levels is imperative. Through increased communication with maintenance workers, a symbiotic relationship is formed which strengthens the design and long-term maintenance of projects. Installers and maintenance workers will have an increased sense of ownership and commitment to provide quality maintenance over the life of the design.

Pedro and Cornelio are representative of many landscape maintenance workers that have significant lived experience, sometimes described as local knowledge, but do not have a voice in decision making. Hierarchical structures within landscape professions have prevented Pedro and Cornelio from expressing ideas which could improve the landscape architect’s design and the superintendent’s maintenance schedule. Engaging maintenance workers in the design process takes time, but the end result is a holistic design that safeguards the project for years to come.

Eduardo Baca was born and raised in San Jose California, served in the U.S. Army as a Cavalry Scout where he spent 15 months in theatre, and moved to Southern California to pursue a B.A. at the University of California, Irvine. He comes to landscape architecture with a background in political studies, international relations, and landscape construction. As a Masters student studying landscape architecture at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, Eduardo worked as a Foreman at an Orange County golf club applying collaborative design in landscape plantings. He plans to cultivate his interest in community design throughout his professional practice.