Property or Person? Rights of Nature as a Pathway to a More Just World

Hannah Kaiser | January 25, 2022

Frankie Myers, Vice Chairman of the Yurok Tribe in Northern California, shares a story in which Re-way, a spirit that lives in the Klamath river, said to Old Aunt Queen: “‘… if there ever comes a time when there’s no more salmon in the river, there’ll be no more need for Yurok people here on Earth.’ That’s what [the river] means to us as a people”. Myers is expressing a widely-held perspective among indigenous groups – that the natural environment is synonymous with their very existence as a people and a culture. This existential interdependence is just one of the reasons why the Yurok Tribe declared rights of personhood for the Klamath River in the fall of 2019. The declaration follows a small but growing global trend to recognize the animacy of the natural world and its inherent right to life.

Much in the same way corporate personhood works to protect the rights of corporations, environmental personhood is seen as a way to extend legal protections for entities such as rivers, lakes, or ecosystems. The movement builds on evolving theories of systems-based ecology and seeks to change the way we interact with natural communities at a fundamental level. Rather than focusing on protection, which objectifies the environment as resource, implies ownership, and has not stemmed the anthropogenic drivers of climate change, the “Rights of Nature” as expressed through environmental personhood addresses the interconnectedness of environmental degradation, climate change, and those most vulnerable to it’s effects.

The Rights of Nature Movement

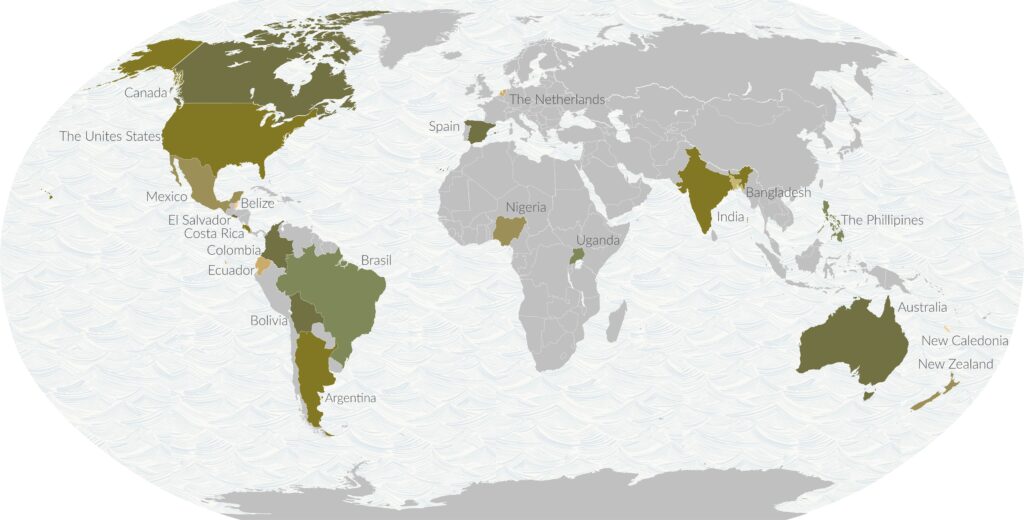

Initially posed as a question by University of Southern California law professor Christopher Stone in his 1974 book Should Trees Have Standing?, the Rights of Nature conversation has spread throughout the world as a means of granting status to natural entities and incorporating indigenous worldviews into modern legal frameworks. In 2008, Ecuador’s constitution was the first to codify the rights of Pachamama (Mother Earth) and in 2017, the Whanganui River in New Zealand was the first river to gain legal personhood. In the U.S., Indigenous tribes are adding to this list, including Ojibwe recognition of Wild Rice in Minnesota and the Yurok’s efforts to defend the rights of the Klamath River.

Stone posited that if a natural entity has rights of personhood, then it cannot be owned. But who is responsible once personhood status is granted? The trans-boundary nature of many of these entities makes this a complicated question for global political and legal frameworks rooted deeply in property rights. Since I am not a legal scholar, the nuances of interpretation and application of the laws are beyond the scope of this article. But our changing relationship with the more-than-human world is for all of us to consider.

Shifting Relationships

In his 1996 book, The Spell of the Sensuous, David Abrams explores the worldview that humans are separate from nature and imagines ways to re-weave us back into the Earth’s systems. He suggests that what we perceive is essential to our understanding of the world and when philosophers drill down on the everyday human experience, an undeniable reciprocity emerges. The physicality of our bodies is important here. Our hand is able to touch something only because it is also touchable. As Abrams states, it is “entirely a part of the tactile world that it explores” (p. 68). Extrapolate this to our other senses and a world emerges that is as equally aware of us as we are of it. See the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy for an overview of phenomenology and the nitty gritty philosophical arguments about “the way we experience things, thus the meanings things have in our experience.”

These ideas parallel certain Indigenous worldviews that value systems of reciprocity and responsibility with the natural world. In his 2018 paper Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice, Kyle Whyte describes Indigenous notions of interdependence as both a sense of identity and a responsibility in which ”…nonhumans have their own agency, spirituality, knowledge, and intelligence” (p. 127). This relationship is important as Whyte describes how settler colonialism is “a form of domination that violently disrupts human relationships with the environment” and therefore is also a form of injustice. Can the ascription of personhood bring this concept of environmental degradation as violence into the legal system? Can it offer a way for Indigenous people to claim environmental wrongs as akin to human rights violations?

As we begin to address these environmental and human rights injustices, a more figurative approach might be part of the way forward, as language is an important shaper of our worldview. In her 2013 book Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer explores how English diminishes animacy: “Biologists have widely adopted the convention of not capitalizing the common names of plants and animals unless they include the name of a human being or an official place name…This seemingly trivial grammatical rule making in fact expresses deeply held assumptions about human exceptionalism, that we are somehow different and indeed better than the other species who surround us. Indigenous ways of understanding recognize the personhood of all beings as equally important, not in hierarchy but a circle” (p. 385). It is through attention to everyday experiences, language, and a broader interpretation of community that we will begin to change this narrative of separation.

Perception and the Built Environment

In her book Welcome to Your World, Sarah Williams Goldhagen researches the the science of cognition, perception, and the human experience as it relates to the built environment. She writes: “Our minds are changing and quite literally being shaped [sic] by our experiences in the physical environments in which we live.” Our experiences with a wild and scenic river as compared to a highly channelized urban stream influence our goals of an equitable and vital world. Environmental personhood suggests the river deserves the benefits of these goals as well.

Consider that designers are embracing the therapeutic effects of nature in hospital designs, green schoolyards, and a growing inclination to bring wild nature into our daily, sensuous lives. Other design approaches seek to directly incorporate the animate world. For example, living shorelines are, as the name suggests, intended to grow with time. Animal-aided design considers animals much like stakeholders. While it can be argued these are still human-centric approaches with people as the primary beneficiaries, they are important steps in restoring our sense of place in the web of life.

A Pathway Forward?

In 2011, the rights of the Vilcabamba River in Ecuador were upheld in court when a road building project that was dumping detritus into the river was deemed in violation of the river’s rights. This was the first legal victory for the Rights of Nature and a hopeful sign that our relationship with nature is transforming into one of mutual respect and acknowledged co-dependence. It is at once a radical departure from property rights and human exceptionalism as well as an overdue recognition of long-held Indigenous worldviews. The implications of a nature-based, rather than property-based, conception of the world ripple out to conversations on environmental justice, climate change, and human rights, some of the biggest questions we collectively face. The movement for the Rights of Nature is a step towards this systemic change that feels sorely needed these days.

Hannah Kaiser is a graduate student in the Master’s of Landscape Architecture program at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.