Finding Common Ground in an Anti-Intellectual World

Michael Gallagher | February 14, 2023

For a brief period of time after completing my bachelor’s degree in environmental studies, I worked as a canvasser, selling products for 2 different solar companies in New York. I had minimal exposure to the complexities of solar technology, and absolutely zero experience in sales – particularly in convincing homeowners to make very large investments in their homes. The vast majority of doors I knocked on resulted in no response. Those that did answer the door, often responded with a yell: “mom, dad, there’s a man at the door!” Then I had to prepare myself for the wide variety of moods, personalities, and beliefs within that 5 to 30 second period while I awaited the adult’s arrival. I would try to find a way to relate to someone that may be vehemently opposed to solar panels or environmentalism, concerned about aesthetics, cost, roof damage, or simply me as a human being knocking on their door and invading their privacy. This experience did not teach me about the efficacy and benefits of installing solar panels; I did not learn more about financing options for solar panels; I did not learn more about the massive responsibility of owning a home. What I did learn is that most people loathe the sounds of their doorbells; I learned that canvassing is a very lonely and challenging job that did not suit my skillset; but most importantly, I learned how to speak to and relate to people that were totally opposed to no matter what I had to say or offer.

This last point is important for those of us who seek to address our present environmental crisis. In an ever-growing world of polarity, full of resistance to change, we, as designers, planners and community organizers need to relate to the communities in which we work . The ability to hold difficult, controversial, uncomfortable conversations is an essential skill that we must develop in order to work effectively in the public realm. A growing trend toward anti-intellectualism in American society is making this skill more important, and more challenging.

Why has anti-intellectualism become an increasingly common sentiment?

Resistance to change or bold new ideas is nothing new in our society. Aldo Leopold describes this phenomenon over 80 years ago in his timeless environmental treatise, A Sand County Almanac. Leopold outlines the wide acceptance among scientists that the topsoil in Southwestern Wisconsin had seen years of degrading quality which threatened long-term production. The solution proposed by these experts was a 5-year voluntary effort on behalf of the farmers to help return the topsoil to a healthier condition. In return, the farmers would receive free labor and specialized machinery in order to complete the conservation effort. Although the practice was widely adopted by farmers at the start, Leopold notes that by the end of the 5 years this effort to infuse science into farming had been largely abandoned, and that “the farmers continued only those practices that yielded an immediate and visible economic gain for themselves” (P. 244).

The disconnect between the advice of experts and rural residents is not a novel story, as Leopold’s anecdote clearly shows. What is new is that many people who are not from and do not live in rural areas are beginning to identify with rural culture and a growing sense of anti-intellectualism. Kristin Trujillo writes about this trend in a recent article in the journal Political Behavior. She argues that rural social identification, a psychological attachment to being from a rural area or small town, contributes to anti-intellectualism and a distrust of experts. Further, she argues that this psychological attachment is not limited to those who actually live in rural areas, but includes those in urban, suburban or exurban communities that identify with rural culture.

As designers, planners and community organizers, this means that we may increasingly encounter people that are pre-disposed to react negatively to our work, perhaps because we have a degree, are perceived as having some expertise, and are perceived to be out of touch with reality – which admittedly may be the case in some situations. If we hope to overcome this increasing anti-intellectual sentiment, how must planners, designers, and community organizers approach engagement with communities?

Facilitation as a Strategy for Community Engagement

Traditional forms of community engagement, most notably the public hearing, evoke scenes from the NBC show Parks & Recreation (2009-2015) where town members vehemently oppose town proposals, berate the facilitators, and raise questions regarding highly specific and questionable issues. While this example parodies the public hearing, it is grounded in some reality. Planners or outside consultants often present their analysis of the situation and interpretation of what the community needs at these hearings, based on their expertise. This places the community in a reactive position, faced with potential changes to their communities or their daily lives. While the public hearing allows for structured community input, usually in the form of speaking for up to 3 minutes, it reinforces the expert vs. community member dynamic that foments anti-intellectualism. Community members are left wondering why their knowledge of the situation was not sought earlier in the process and because decisions frequently follow quickly after the closure of the public hearing, suspect that a decision has already been made based on advice of outside experts and their input was meaningless.

If the goal is to ease tensions between experts and community, for the purposes of countering anti-intellectualism and gaining broader support for policy, I propose embracing a mindset as a facilitator of a conversation, as opposed to an expert presenter. This may including moving the conversation out into peoples’ own neighborhood, as opposed to city hall or a traditional seat of power. While this option is more time consuming, it shows a genuine effort that the project team wants the community to feel comfortable, is open to feedback and is willing to make the effort to hear their concerns. The Arkansas Fish and Game Commission used this strategy to connect with duck hunters in the state about new conservation strategies. Research has found this technique also reaches people that may not have the time or ability to attend various town hall-style meetings due to the wide variety of demands that we all encounter in modern life, thus allowing the project team to get a better grasp on the mindset of the community that the proposed project is going to impact.

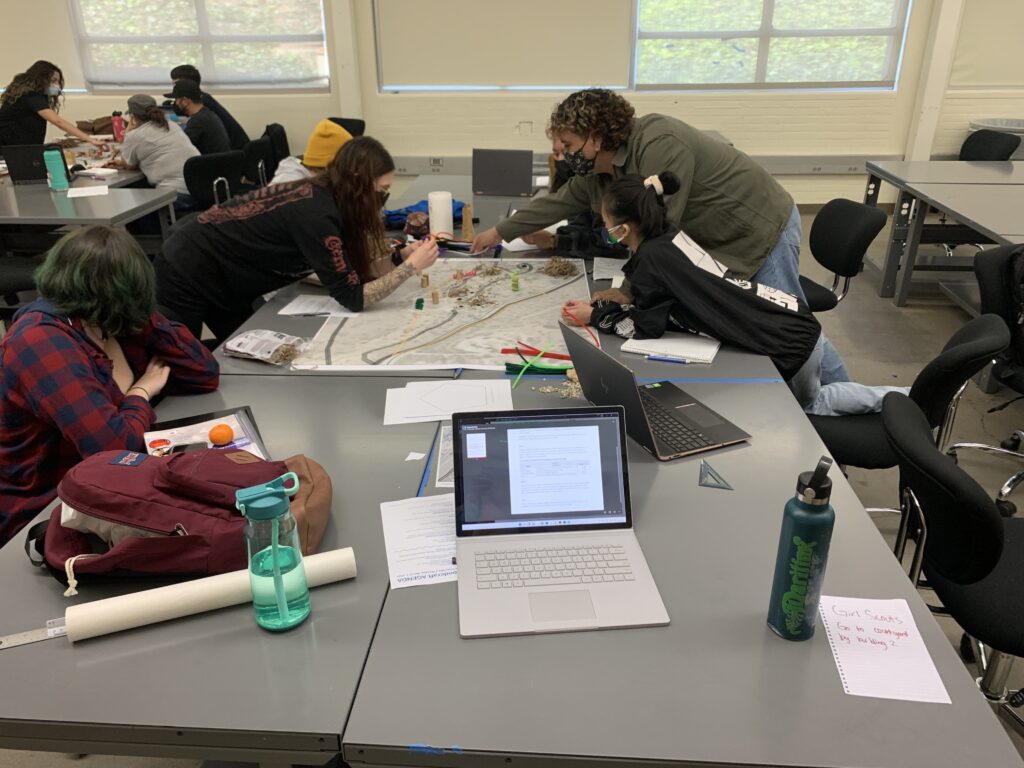

Embracing the mindset as a facilitator of a conversation requires understanding the wants and needs of the community as the community see them, even if our professional knowledge suggests otherwise. This approach goes hand in hand with empowering community members with a sense of ownership over the project. In the event that there is disagreement between community members and expert opinion, facilitators should empathize, understand and try to relate to the community’s concern in order to develop a work plan that will address and incorporate those concerns into the final design itself. Learning why community members are skeptical of a project proposal helps the facilitators uncover deeper root causes that may be afflicting the community that can potentially be addressed. By seeking out root causes of issues and addressing them, the final solution will result in a more meaningful, representative, and inclusive space for the community. This type of community engagement is outlined in detailed in “Mapping the Living Sphere” in the inclusive community design workshop handbook, Design as Democracy. In this case, the facilitators worked with the numerous stakeholders to find common ground through an overlapping mapping exercise.

By immersing yourself into the community and genuinely trying to understand their needs from their perspective, the facilitator is able to develop a more thorough and well-planned project, suiting the variety of needs that every community possesses. It also increases the likelihood that your knowledge as an expert will be valued, when the community relates to you as a person who shares and understands their concerns – there is no more effective way to develop a meaningful and community-oriented project.

Mike is an ocean-loving Southern California transplant who developed a fascination with the California deserts since moving to the region 4 years ago. He earned his undergraduate degree in Environmental Studies from Siena College where he developed a keen interest of how society and economics interact with the environment. Since starting his masters, he has become more interested in how design can benefit both society and the environment focusing on issues related to social and environmental justice. In his free time, you can find Mike surfing, reading, and attempting to do ceramics.