The Thick Injustice of Park Inequity

Graham Feltham | March 21, 2023

Prior to moving to Los Angeles, California for graduate school, I lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for a decade. Initially, I lived in West Oakland for several years prior to moving the short distance to Berkeley. It was clear to me immediately upon moving that my change of address and increase in monthly rent corresponded directly to greater access to green space. When I lived in the heart of West Oakland in 2013, the closest park was at least twenty minutes away on foot. Many of the sidewalks were crumbling and poorly maintained, and basic pedestrian infrastructure, like crosswalks, were scarce. Bicycle infrastructure was non-existent at the time. Aside from being few and far between, West Oakland’s parks were visibly underfunded, and I played pickup basketball on battered hoops without nets on cracked asphalt.

After moving to Berkeley, I was able to walk to my choice of parks, strolling a few blocks along well-maintained, generous sidewalks buffered from traffic by an extensive system of bike lanes. There were three parks within five-minute walking distance, all of which featured newly installed sports equipment, significant tree canopy, healthy plant material, and recreational programming for the community. Proximity to Berkeley’s parks afforded me a sense of freedom that had eluded me in West Oakland; the ability to walk to a green space gave me the power to shape my daily experience in a way that was impossible when surrounded by the expanse of concrete in West Oakland. The stark disparities between these two places, only a few miles apart, made me wonder what was causing this inequity.

West Oakland’s past and present are indelibly marked by racist policies implemented during the City Beautiful, New Deal, and post-WWII eras. What was initially a vibrant neighborhood of color was radically altered by the imposition of two freeways, both of which were a result of the ‘urban renewal’ characteristic of U.S. cities following WWII. These elevated roadways bisected what had been a bastion of Black American culture and resulted in the displacement of 5,000 households, all to the advantage of wealthy, predominantly white residents who’d fled to the suburbs, placing the need for additional autoroutes to and from the financial districts above the needs of the existing community. Additionally, a new elevated station and raised train tracks further fragmented the area, exemplifying the prioritization of the suburbs over the inner city. The division of the neighborhood contributed to disinvestment, further cementing the lack of park land in West Oakland.

The fact that discriminatory housing policies have shaped inequities in park access by restricting where low-income people of color can live cannot be disputed. Although access to green space has improved in some instances, it has largely been a result of the residential location choices of affluent white residents, as opposed to a drive for equity across racial and economic lines. Such was the case with West Oakland.

Learning from Denver

A recent study by researchers from the University of Illinois may shed light on what I observed in West Oakland. Allesandro Rigolon and Jeremy Németh examined processes contributing to uneven park access in Denver, Colorado. Denver’s social stratification and distinct neighborhoods are representative of many cities across America, and the factors contributing to Denver’s injustice are useful in understanding inequities elsewhere in the United States. According to Rigolon and Németh, “inequities in park acreage produced during the City Beautiful and New Deal eras persist today, highlighting the challenges of reversing the long-lasting legacy of racist public policy” (P. 4). They argue the City Beautiful era was defined by a top-down approach in which vast urban green spaces were designed and implemented with the goal of attracting well-heeled citizens to their environs. The New Deal era involved similarly grandiose projects, made possible by the labor of the poor but intended primarily for the benefit of the wealthy.

Further research by the World Resources Institute supports Rigolon and Németh’s position that historic policies improved quality of life for the white elite to the detriment of the lower castes. They write “The correlation between urban tree cover and income is well-documented in cities around the world…infrastructure decisions made decades ago unfairly benefit rich neighborhoods and can be a driver of current and future inequality.” Such continues to be the case, with economic benefit remaining the primary driver for access to green space.

Following the excess of the City Beautiful and New Deal Eras, the Post-World War ll period in Denver was defined by racist housing and zoning policies which resulted in further disparities of access along economic and racial lines. Indeed, one such zoning policy ensured that no low-income people could live near parks or green space, explicitly codifying Denver’s extant demographic distribution in concrete terms. Zoning became progressively less restrictive away from well-established parks, perpetuating the status quo of wealthy white park-rich neighborhoods adjacent to low-income areas populated primarily by people of color that had far less park land, a process repeated in many places around the country. To this day, neighborhoods with higher percentages of black and Hispanic residents in the United States have less green space. Others have noted that less green space and less vegetation may become even more critical for the health and well-being of marginalized communities as climate change worsens.

Rectifying “Thick Injustices”

These policies and practices which were commonplace across the United States, extended over decades, have cemented the inequities in green space access along racial lines, and suggest a radical re-organization of the urban framework, if the injustices are ever to be rectified. Rigolon and Németh describe these conditions in Denver as a “thick injustice” because “deep rootedness of urban injustice obscures privilege and disadvantage, [and] also makes it difficult to ascribe blame or responsibility to certain parties” (P. 11). Rather than ascribing blame for these situations, it may be more useful to conceive of ways to separate from it, abandoning it in favor of policies and projects contributing to equity of access.

The World Resources Institute argues that those interested in achieving equity should first seek to ‘establish strong political leadership’, with the aim of prioritizing disadvantaged communities, protecting long-term social benefits over short-term economic interests. Additionally, they state that communities must be engaged meaningfully, to ensure local buy-in and agency. Finally, they argue for the need to develop innovative funding models to help cities put green space in underserved neighborhoods while protecting community ownership and preventing gentrification.

Rigolon and Németh propose five ways to realize equity of access. First, equity must be an explicit goal in all decisions, exposing racist outcomes of policies while doing so. Second, there must be an effort to engage historically marginalized groups in the planning process to combat the disenfranchisement resulting from years of racist and classist policies. Third, professionals should work towards collaboration between the fields of land use, transportation, public works, and housing. Fourth, communities must prod their elected officials to prioritize park equity over developers’ interests and, finally, they must conceive of creative strategies to increase park access for marginalized people. This framework offers a useful strategy for dismantling the systemic structures that have given rise to inequalities, but such a strategy is predicated upon the building of political power, called for by the World Resources Institute.

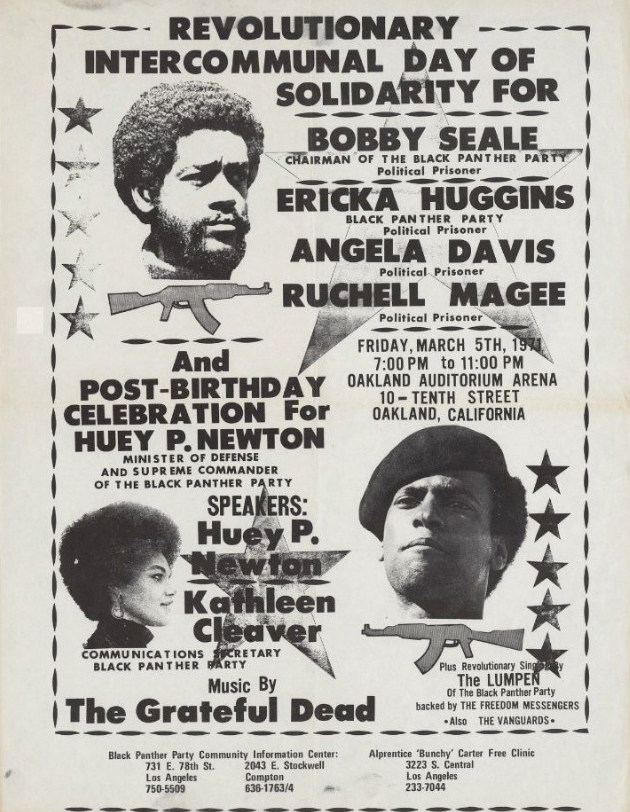

The Black Panther Party, founded in 1966 in West Oakland, was an effort to build local power as a response to the same racist policies that restrict access to green space today. The Party took a holistic view of justice that addressed housing, nutrition, education, violence, freedom, and notably local power and determination. The Party attempted to operate outside of the status quo to redistribute power and were vilified by the white establishment. The violent response to the Black Panthers illustrates the lengths to which the establishment will go to maintain the status quo, as well as the reality of what the fight for equity means for those working on behalf of the oppressed.

The history of places like Denver, West Oakland and organizations like the Black Panther Party provides crucial lessons to those who wish to combat the racial polarization of American cities. The “Thick Injustices” extend beyond the issue of park land, into housing policy, zoning, transportation, and funding strategies at the Federal, state and local levels. Unless we take a holistic view that understands the relationship between these issues and seeks to dismantle tactics that promote inequality, we cannot hope to rectify inequities in green space access or in access to other vital resources. Perhaps most importantly, political power must be built by those communities most affected by these inequities, so that their interests are prioritized.

Graham was born in Upstate New York and spent his formative years touring the East Coast in punk rock bands. The post-industrial cityscapes of the rust belt form the backdrop of his interest in landscape design, and he hopes to be able to put the skills he’s gained from the MLA program at Cal Poly Pomona to use in cities suffering from disinvestment nationwide. When he’s not thinking of creative ways to rejuvenate urban space, Graham can be found carving utensils out of wood, playing music, or kicking a soccer ball against a wall. Graham plans to move back to the East coast after completing his graduate degree to make the change he wanted to see growing up.